Utterly biblical rain for nearly a week, the ground, even in the garrigue garden, is drenched and squelching- it is not to be touched or worked on and so indoors I have been. And so the mind turns to…’a mild form of mania’, as the ground-breaking American landscape gardener, Beatrix Farrand (1872-1959), said of herself in her young years. She was describing her young self as she battled to find a foothold in the entirely male echelons of landscape gardening and architecture. Of which more in a bit.

I have been reading Sandra Lawrence’s excellent book about Ellen Willmott (1858-1934), which is written with passion and verve underpinned by exhaustive reseach and scholarship- a great combination of skills. And I was struck by how many threads interconnected Ellen and Beatrix’s lives even though 14 years separated their births and they never met.

Ellen was born in 1858 and Beatrix Farrand in 1872, so that their lives really did straddle the two centuries when landscape design and gardening emerged into the limelight. Even though only 14 years separated their births, in some ways, Beatrix became what Ellen was unable to be- by her thirties, she was forging a fully independent professional life as a landscape gardener, having been a founder member of the American Society of Landscape Architects, and the first female admitted to membership.

I had briefly touched on them both as significant women bridging the 19th and 20th centuries when I did the garden history section of my design diploma, but I have really enjoyed the last few days of research imposed by the weather, and so you are now getting the full effect of it, dear reader. I have ordered the revised edition of Judith Tankard’s biography of Beatrix, so my mild mania continues.

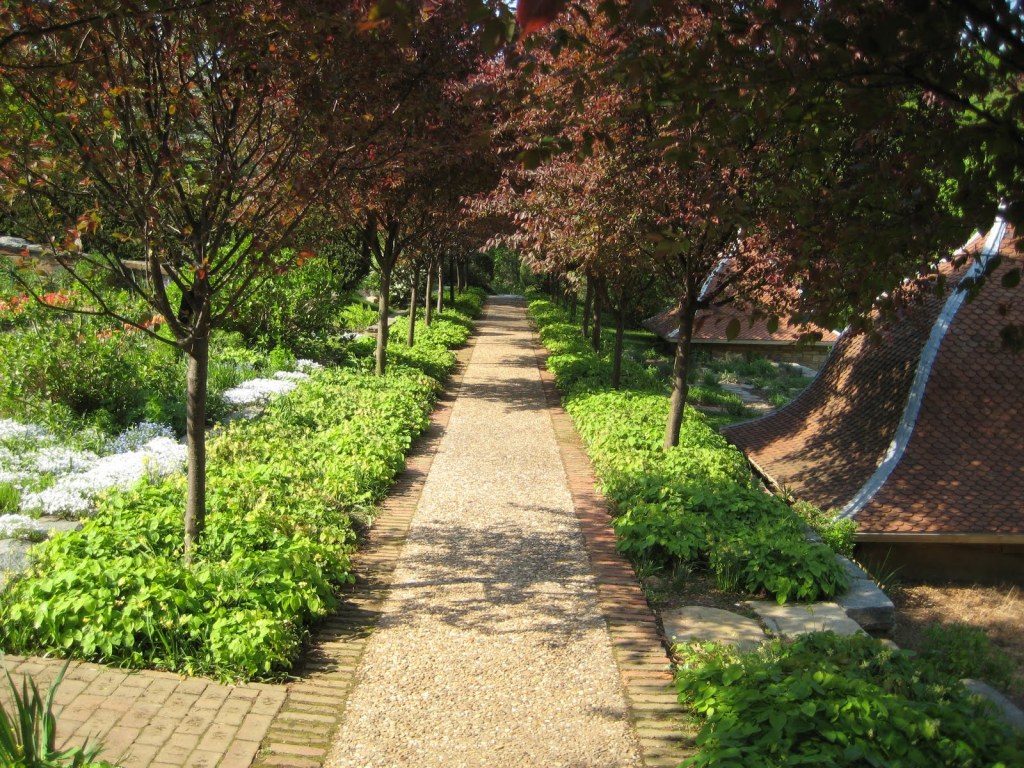

I was reminded of Beatrix way back in 2014-5, when I visited Biddulph Grange, you can follow the link for that connection in my head. Beatrix Farrand was very partial to English Ivy as groundcover, especially if gently sculpted as at Biddulph Grange in the UK. At Dumbarton Oaks, her huge Georgetown, Washington DC project, today the team are largely replacing the ivy as it has proved to be too invasive, as can be seen in the Prunus Walk, where the underplanting is now based on epimediums.

But let’s start with their early lives. Both were born into wealth. Ellen lived most of her life with an inconceivable extravagance backing her many talents and interests, from fashion to antiques, from woodworking tools to photography, from plants, funding important plant hunting expeditions and creating huge personal gardening projects across three countries. In a way, Ellen never grasped or accepted the limits of her wealth, and in the Victorian age, there was no professional exit for her which might have taught her that.

Beatrix also came from ‘Gilded Age’ wealth, and an incredibly useful network of wealthy connections, but she knew the social and financial price of failure as a young teenager when her parents scandalously divorced, and perhaps this fired the engine of her determination to make her professional life create independence.

Both women were very skilled at keeping contact, and deep friendships with other influential and significant plantspeople, botanists, scientists and others- importantly, they were able to inspire mentoring, encouragement, sometimes a little manipulation from powerful male colleagues and mentors. Both, for instance, were significantly prompted and supported by Charles Sprague Sargeant, the Director of Harvard University’s Arnold Arboretum in Boston, a botanical titan of the late nineteenth century. Beatrix met him through family connections, and despite the fact that professional education and training in gardening and landscape was still closed to women, he invited Beatrix to study and train with him. He supported her in her first tentative steps in taking paid commissions and encouraged her to travel in Europe, to study great works of art and broaden her experience and contacts.

Around the same time, Ellen had started a regular and detailed correspondence with Sargeant in which she discussed her gardening projects, plant development work, her botanical successes and experience in plant propagation and her interest in plant-hunting in China in particular. Sargeant was quick to realise that Ellen could provide both money and professional partnership for plant and seed collecting expeditions, and together they were instrumental in making happen, amongst others, Ernest Wilson’s groundbreaking expeditions to China. Ellen became reknowned for her skill in germinating seed sent back by Wilson from these expeditions.

Whilst in England in 1895 on her travels, Beatrix was tremendously inspired by meeting the very old William Robinson and also Gertrude Jekyll. Robinson’s work in relaxing the rigid frame of acceptable Victorian gardening style and fostering native and perennial plants in more natural combinations in sympathy with the prevailing Arts and Crafts movement was a great inspiration. Similarly, visiting Jekyll at Munstead Wood introduced her to thinking of painting with plants in coloured drifts.

By the same year, 1895, Ellen’s photographs were regularly published in Robinson’s famed periodical ‘The Garden’. Despite his advancing years, William Robinson was the only horticultural publisher who saw the immense potential of photography as a selling point- and Ellen, by now an exceptionally skilled photographer, was a key contributor. She had already created her immense and extremely well received rock garden for her huge alpine collection at Warley Place, her childhood home, and was busy developing her garden at Tresserve near Aix-les-Bains in the Savoie region of France. She was two years away from being recognised by the Royal Horticultural Society, with Gertrude Jekyll, as the first two women to receive the society’s highest honour, the Victoria Medal of Honour

Two years after the RHS honoured Ellen in 1897, Beatrix set up her business in her mother’s house in New York on her return from the Europe trip, and over the next four years, she built her business as a landscape gardener, culminating in her work being honoured by the becoming the first founding woman member of the American Society of Landscape Architects in 1899.

After 1899, their lives moved in different directions. Beatrix continued working with enormous professionalism and diligence, often criss-crossing the US by train to supervise work projects, working with her secretary alongside, during the journeys. She completed more than 200 garden projects, with, perhaps, her most enduring legacy being the gardens at Dumbarton Oaks, Washington DC.

Ellen, by now the developer of three exceptional gardens, Warley Place in the UK, Tresserve in France, and Boccanegra in Italy, had also never quite realised that her money, once a bottomless purse, would run out, and the last part of her life was spent frantically, and unsuccessfully, trying to manage the debt. The only garden that we can now see of hers, is Boccanegra in Italy, which has been painstakingly restored by the current owners, Guido Piacenza and Ursula Salghetti Drioli. She was born before her time in a way, and is only now being remembered as the supremely talented garden maker and plantsperson that she undoubtedly was.

Beatrix Farrand is better remembered and her legacy can be seen in several gardens, including the iconic Dumbarton Oaks, and her papers and designs are largely intact and kept at the University of California in Berkeley.

Curiously enough, we owe it to Beatrix Farrand that Gertrude Jekyll’s collected papers were saved for posterity. Beatrix bought the collection in 1948 for her own enjoyment and then donated the Jekyll documents along with many records of her own work to Berkeley.

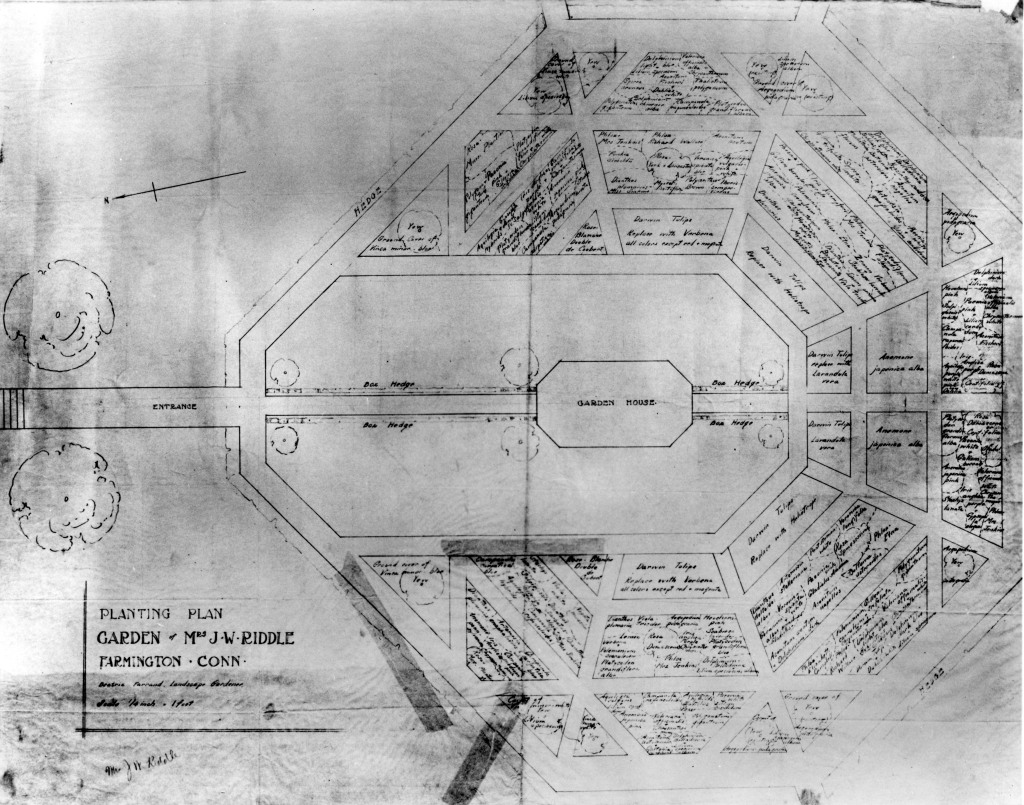

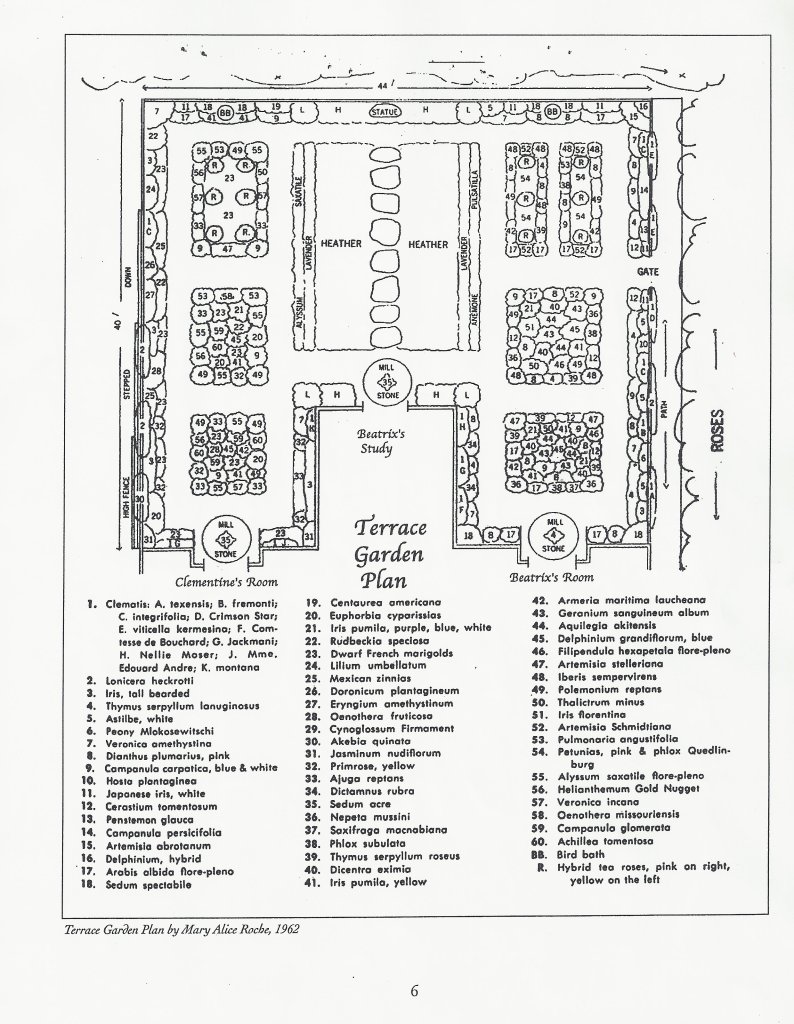

Two small memories of Beatrix: The Sunken Garden, below, was created from Beatrix’s design after her death, and the small but lovely Terrace at Garden Farm, has recently been restored. Garden Farm was Beatrix’s last home.